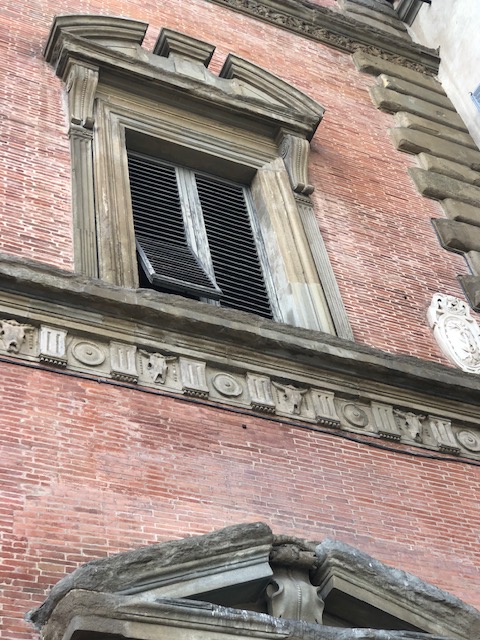

On a corner of the Santissima Annunziata square stands the Palazzo Grifoni Budini Gattai. It is the only exposed red-brick edifice in all of Florence, distinguishing it as a structure of curiosity and elegant beauty. On the second floor to the right is a partially opened “jalousie” shutter, originally from the Italian gelosia, meaning jealousy, as the screens shield interiors from prying envious eyes. Even the piazza’s imposing bronze statue of Ferdinand I gallantly mounted on his horse has the Grand Duke staring at the curious open-shuttered window. The shutter has remained in this position for almost 500 years. Dare anyone try to close it and there might very well be hell to pay, for within, it is said, resides the spirit of La Donna Grifoni, the bride of one of the building’s original owners, who demands that the window and its gelosia remain open, forever.

The square was first laid out in 1298 and was named Santissima Annunziata after the glorious mid-13th century basilica, which heralds the square. The current design is the executed vision of Brunelleschi from 1419, even before the mastermind devised his famous cupola of the Duomo, which floats miraculously above rooftops just down the way. At the time, Brunelleschi was creating plans for the Spedale degli Innocenti, the foundling hospital, an orphanage and a magnificent edifice on the piazza as well as a touching reminder of the importance of Florence’s philanthropic past. The square is also a testament to the egalitarian Renaissance, given its sense of harmony and welcome from all sides. As for the Palazzo Grifoni Budini Gattai opposite the basilica, construction began in 1561 by another leading Florentine architect, Bartolomeo Ammanati, an acclaimed student of Michelangelo, while the palazzo was completed by Bernardo Buontalenti, who also designed the inner courtyard and gardens. While Grifoni’s “sister” palazzo next door was contracted much later in the harmonious style of the square, a considerably younger imitation (and perhaps less effective imitation of its brother, the Palazzo Grifoni Budini Gattai), the Grifoni Palazzo, featuring exposed brick and “pietra”, is nobly majestic, seemingly to its manner born.

Up until only 20 years ago, the palazzo was the seat of the Tuscan government, without much opportunity for the curious to visit the interiors. Today, those interiors can be rented for events: weddings, fashion shows, dinners and garden parties. Speaking of the garden, it too was designed by Michelangelo’s student, Ammanati, and it is the natural extension of the inner courtyard’s loggia. Ammanati also designed the whimsically grotesque fountains. And just above one such grotesque flanked by centuries-old protective walls, one notes that the neighbor has an interesting cupola. When one asks the building’s director, a lovely lady with fiery red hair by the name of Franca Quercioli (“Italian? I am not Italian. I am not even Tuscan. I am Florentine!”) what is beneath the neighbouring cupola, she responds with that miraculous combination of local “above-it-all-ness” and a twinkle in her eye: “David”.

Suddenly, in the strangest way, world icons become real people. For the neighbor is the Accademia and “David” is Michelangelo’s. A sculptor and his student are neighbors here, connecting through art and time in a neighborhood garden with ancient camellias, wisteria, banana trees, and even an unusual “monument to a missing tree”, installed in 1908 in memory of an ancient camphor tree that had dried up one winter. For all his effect on the world, never did “David” feel more human than at that moment as the “fellow” next door overlooking his student’s garden. The loggia, once entirely open to the garden itself, now has grand arched glass windows, allowing for another glamorous interior in the centre of Florence. The palazzo’s entertaining rooms feature a wood carved and gilded dining room, which opens to a secondary inner courtyard, grand salons decorated in 18th-century style with windows onto the garden, and a sweeping staircase and piano nobile, which is now the photo library of Kunsthistorisches Institut in Florenz, the Max-Planck Institut dedicated to the research and history of art and architecture with a special commitment to young academics in the field. The institute, separate from the rentable spaces in the palazzo, is not readily open to any passerby. It requires finding a way in by speaking with the librarian perhaps. It might be worth the effort, for the late-19th century restoration is entirely intact and stunning. While the palazzo has been in the hands of the wealthy Florentine builders, the Budini Gattai family, since 1890 and family members still own various apartments rooms and floors, it was Ugolino Grifoni, secretary to the Grand Duke of Tuscany, who commissioned the construction in the mid 1500s. The edifice remains exactly as it was upon its completion in 1564, except for a top floor that was added several centuries later.

As for the open shutter on the right corner of the piano nobile, near to the Grifoni coat of arms, the story goes as follows. One of Ugolino Grifoni’s scions married his young bride, but shortly after the wedding, the groom was called off to an unavoidable war to protect Florence from threatening forces. His young bride sat by their window and waved goodbye as the groom made his way down the piazza on his horse. She continued to sit on a bench by that same window every day, awaiting her young love’s return. After several weeks, word arrived that the young Grifoni had been lost in battle. Not wanting to believe the news, the young bride remained by the window, the shutters open, reading, sewing, drawing and looking longingly at the piazza, sure that one day her husband would return. As the years passed, with no sign of her husband, the young bride grew older, but every day she could still be found at the window, waiting for her love.

When the woman died at the turn of the 17th century, the Grifoni household thought it best to attend to the woman’s belongings, organizing what she had left behind, putting her books and personal items in order. In so doing, one of the family members closed the window and the shutter where the widowed bride had spent her entire life waiting for her beloved. The moment the shutter was closed, so the story goes, books began to fly off shelves, paintings fell, furniture scraped the floor, and the Grifoni family was terrorized. It was then that one relative rushed to the window, opening the shutter as well. Immediately, the whirlwind calmed down. Able once again to wait for her beloved husband, the bride’s spirit was at peace.

Today, some 500 years later, the window and the gelosia remain open. The shutter has not been closed since that day almost 500 years before when the bride’s spirit let the palazzo’s owners know that she would remain, waiting for her love. Today, as one is guided to the main courtyard door on the piazza Santissima Annunziata by the building director, Franca, while in the archway, one looks up to the second-floor open window and says, “So that is where the bride still sits?” To which the fiery red-haired Franca, with her perfectly elegant Florentine “above-it-all-ness”, says, “Eh, sì.”

And the twinkle in her eyes tells you that she and the centuries-old bride have met.