Bob Marley wrote “Buffalo Soldier” with Noel “King Sporty” Williams, but the song was released by Bob Marley and the Wailers in 1983, two years after the singer-songwriter’s death. It became one of Marley’s most popular songs with its catchy refrain:

I’m just a Buffalo Soldier

In the heart of America

Stolen from Africa, brought to America

Said he was fighting on arrival

Fighting for survival

Said he was a Buffalo Soldier

Win the war for America

Indeed, Buffalo Soldiers are African Americans who have fought for America in every major conflict since the 1860s. Their nickname dates to the time when Black soldiers volunteered to serve in the American West. There are three different explanations about why Native Americans coined the term “Buffalo Soldiers”, whom they considered to be “black white men”. One story goes that it was out of respect for a brave enemy, just as threatening as their “pale face” brothers; another recounts that the Native Americans thought that their dark skin and curly hair made them resemble buffaloes. Yet another says it is because many of the Black soldiers wrapped themselves in buffalo hides against the freezing winters on the prairies.

Almost one million African Americans enlisted in the armed forces during World War II and continued to be placed in racially segregated units with white officers commanding them. Owing to increased pressure from the Black community, the government had finally been forced to change its policy of excluding African American soldiers from combat. So, after nearly two years of intense training at Fort Huachuca, Arizona, the 370th Regimental Combat Team arrived in Naples on July 30, 1944, as advance guard for the soon-to-arrive 92nd Infantry Division, to which it belonged. It was the only division of Buffalo Soldiers to engage in combat in Europe during this conflict. The division, which had seen action in France during World War I, had been called back into service in October 1942, ten months after America entered the war.

Members of an African-American mortar company of the 92nd Division near Massa, Italy. This company is credited with liquidating several machine gun nests. Source: NARA.

The 92nd continued the proud tradition of wearing a circular shoulder patch displaying a black buffalo on a dark olive background as the divisional symbol on its uniforms. The infantry even kept a live buffalo as its mascot at the home barracks in America.

When the troops arrived in Naples, they were shocked by the poverty and destruction on the city’s streets, although many of them had grown up poor in Missouri, Alabama and Georgia, and some could neither read nor write. They were, nonetheless, in tiptop form and morale was high. From Naples, they moved north on foot or in trucks on the heels of the Germans, who retreated from one line of defence to the next along the peninsula.

Once the offensive started on D-Day, 100,000 men out of 249,000 of the American Fifth Army in Italy were pulled out to fight in France. As reinforcements, the Buffalo Soldiers occupied the western side of the Allied front between August 1944 and May 1945. They crossed the Arno river and went into battle to liberate Pisa, Lucca and Versilia, including Viareggio where the 92nd had its headquarters for a period, Massa, La Spezia and Genoa, as well as a host of small towns and villages mainly along the Ligurian coast and in Garfagnana in the Serchio Valley. The British Eighth Army operated on the 200-mile eastern front on the Adriatic, with the objective of liberating the Florence-Arezzo-Bibbiena triangle.

The 92nd faced strong resistance from battle-hardened troops, often in mountainous or mud-soaked terrain. The Germans’ defensive campaign gave them time to build their strongest line of defence, the Gothic Line, by using 17,000 slave labourers. It ran diagonally, coast to coast, across the Apennines mountain range and was peppered with 2,000 machine gun nests, bunkers, observation posts, tank emplacements and minefields. The final breakthrough of the Gothic Line would not come until April 1945 during Operation Olive, also known as the Battle of Rimini, the final Allied offensive of its winning Italian campaign.

Of the 12,846 Buffalo Soldiers who saw action in Italy, 2,848 were killed, captured or wounded. In turn, they captured or helped to capture nearly 24,000 prisoners and received more than 12,000 decorations and citations for bravery, including two Medals of Honor that were not awarded until 1997. Despite this, once they returned home at the end of November 1945, the military establishment unfairly considered their deployment a failure. This was later shown to have been the result of inept or constantly changing leadership.

Throughout US military history, African Americans have faced racial prejudice and segregation because, prior to the 1860s, they were not considered courageous, motivated or trustworthy enough to fight. Having proved innumerable times that this was not the case, the next hurdles were to serve under Black commanders and the right to fight shoulder to shoulder with their white counterparts (and other troops regardless of their skin colour). These last two obstacles were overcome, in principle, when the American Armed Forces officially ended segregation in 1948 and, in practice, when African Americans fought with white Americans in the same units for the first time during the Korean War. Pockets of discrimination in the armed forces may still exist, but the Buffalo Soldiers will always hold a special place in Tuscan hearts as those who fought to liberate the region and break Axis resistance on the Gothic Line.

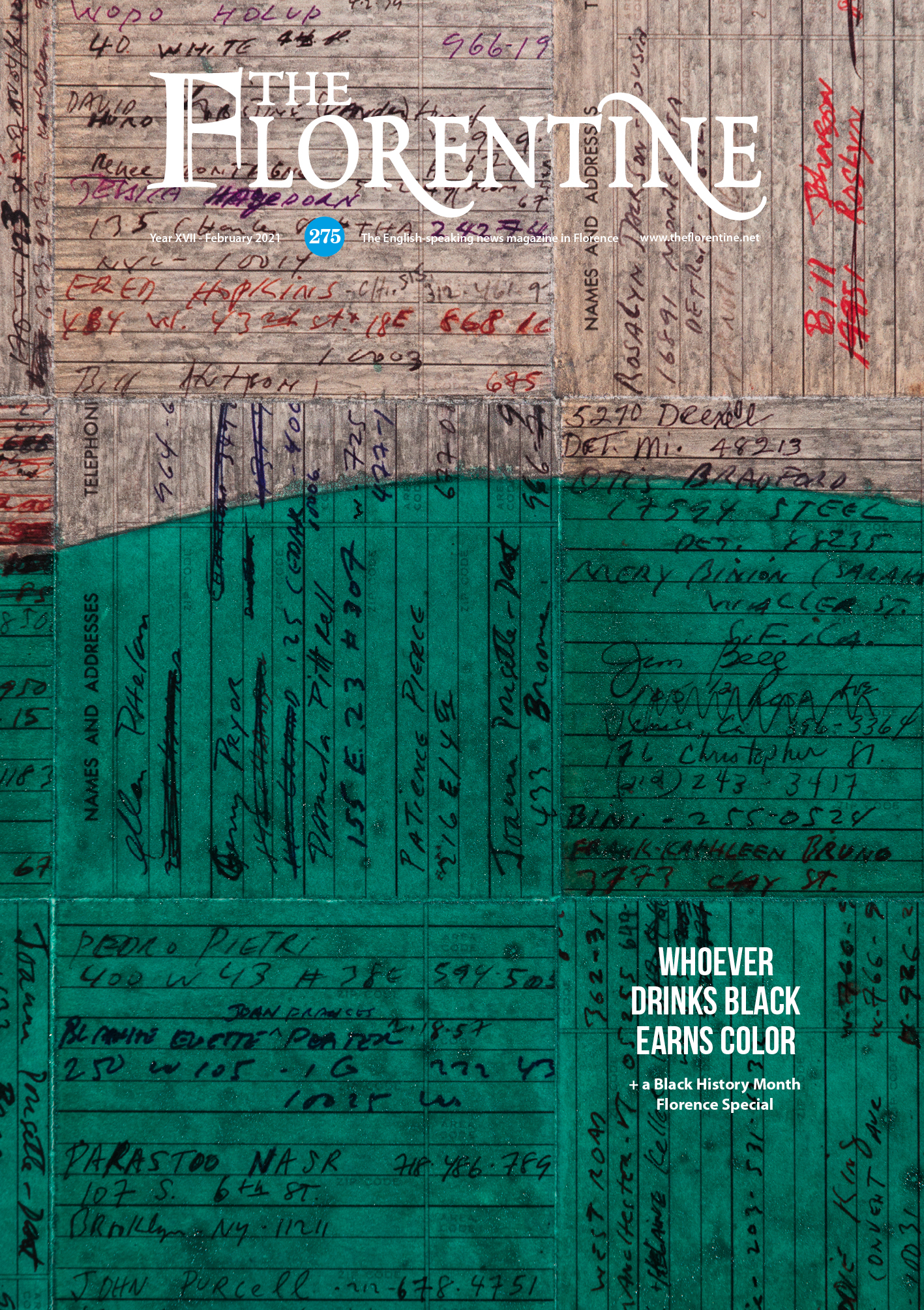

This article was published in Issue 275 of The Florentine: A Black History Month Florence special.