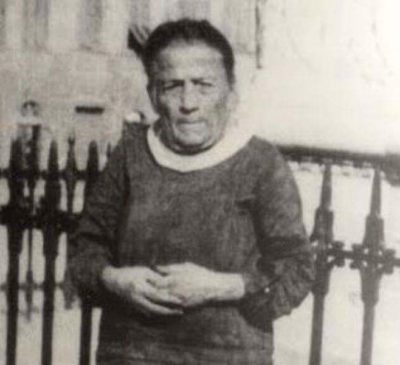

On May 15, 1896, a small, slender woman with a baby in her arms lay down across the tram track in Brozzi, a town on the outskirts of Florence. Her name was Barsene Conti, soon to be better known as “Baldissera” after General Antonio Baldissera, governor of Eritrea. For the month between May and June, she was the trecciaiola, or straw plaiter, who led the first strike demanding a pay rise for women’s work in Tuscany. Her action aimed to stop the transport of straw hats to Florence as her companions boarded the tramcars and set the hats on fire. Hoisting an Italian flag over her head, she and two of her supporters ran along the street, inciting other straw plaiters to stop work and join them. This was extraordinary because these were simple, often illiterate women used to working from home within a domestic cocoon.

Wearing straw hats dates back to ancient times but, by the 1500s, their workmanship in Tuscany had reached such quality that Grand Duke, Cosimo I de’ Medici, gifted them to other sovereigns throughout Europe. By the early 1700s, after much experimentation, Domenico di Sebastiano Michelacci, originally from Bologna but then resident in Signa, introduced a grain specifically for making hats rather than for food. This marzolo grain was sown in barren, dry land that yielded finer straw, hence a finer weave. As it was harvested towards the end of May and early June, it was pulled out of the earth, not cut, leaving the lymph in the stalk. This improved the colour, although the straw was also bleached due to its exposure to the sun and dew. Only the stalk of the upper joint was selected and tied into small bundles, bleached in sulphur fumes, sorted by sizes and prepared for the plaiters. The majority of them were women or adolescent girls because their smaller fingers were the most adept at the job. A hat would normally have 40 rounds of hand-plaited rows sewn together, each of 13 threads. Next, the hats were ironed, glued and dried in drying cabinets until they stiffened. A good quality hat needed four or five days to make, while the finest models could take between six to nine months with wealthy customers prepared to pay a high price for them. They were a fashion status symbol.

In the early 1800s, the villages around Florence produced up to 142 million hats a year.

By 1776, the port of Leghorn had become a hub for English merchants in the Mediterranean basin and Tuscan-made straw hats, initially for women and later for men, soon dominated the market; they were called “Leghorn hats” in the honour of the city. Middlemen, or fattorini, between the wholesalers and the straw plaiters began appearing and, in the coming century, many would become very rich men. During and for several years after the French occupation in Tuscany, exports were expanded to Napoleon’s empire and America. In fact, in 1827, Nathaniel Carter wrote in Letter LXXX of his Letters from Europe, Comprising the Journal of a Tour through Ireland, England, Scotland, France, Italy, and Switzerland that, “Hats of the first quality are sent to France; those of a second to England and the refuse to the United States and northern Europe”. To try and stop this trade, England imposed duty on their importation and advertised competitions to find local alternatives, while the French, because their climate was not suited to growing the grain, set up straw-related businesses in Tuscany. Nonetheless, smuggling and collusion flourished and the hats still manage to arrive at their destinations. It is estimated that, in the early 1800s, the villages around Florence produced up to 142 million hats a year.

By the time of Italy’s unification, Tuscany’s pre-eminence began to wane because of competition from other Italian towns and imports from China, Japan and Java. Three and a half decades later, the hat industry in the region was at its lowest ebb. According to The Times, there were 84,558 trecciaiole, 80,000 of them women who could barely buy a loaf of bread with the money they earned after a long day’s work. Again, Carter describes this in Letter LXXXI, talking about the peasant women he saw in the Tuscan countryside. “We saw groups of them, sitting before the doors of their houses, in villages along the road, or in some cases, in the open fields, busy at their work braiding straw. They lead a most laborious life, subsisting on light fare, and toiling hard.”

News of Barsena’s gesture soon spread and the strike rapidly extended to include straw plaiters in Prato, Fiesole, Impruneta and other towns in the vicinity. Next, the women who made the straw covers for wine flasks in Empoli joined them, along with women tobacco workers in Florence. The new Socialist Party of Italian Workers did not support the strike, nor did the fledgling local labour organizations. Perhaps because the strike was far from peaceful, many of the women’s husbands stonewalled the protest, including Barsena’s, who left her because of it. Not only were the trams attacked but police on horseback broke up a demonstration in Sesto Fiorentino, where the women had thrown stones at a manufacturer’s building and called on the Ginori porcelain factory workers to join them.

Once the strike was suppressed, some of the demonstrators were sentenced to prison terms ranging from a week to a month and a half. As the instigator, Barsena was imprisoned for a year. Once out of jail, she convinced her husband to return to her. The people in Brozzi were not so forgiving and shunned her, forcing her family to move to the Santa Croce quarter in Florence.

Today, 15 companies, some of them dating back to the late 19th century, continue to manufacture Florentine straw hats. In 1986, they formed an association called Il Cappello di Firenze to promote and protect excellence in this traditional craftsmanship.

The “Domenico Michelacci” Straw Museum in Signa traces the history of the life of straw plaiters in Signa with documents and photographs and displays of the tools they used, the plaits they wove and the decorations they made for the straw hats as well as examples of the hats themselves.

It’s situated in via degli Alberti 11, Signa. For further information, see www.museopaglia.it