In the midst of trying times, Florence’s history provides a welcome escape and offers some necessary perspective. Season Three of Medici: The Magnificent is quick to remind us that Florence has recovered in the face of seemingly insurmountable odds before. History often shows us that crisis crafts leaders who forge ahead with a magnificence that, in times of quietude, might go unnoticed. In the Florentine memory, no one’s magnificence is exalted more than that of Lorenzo de’ Medici.

This final season follows a third generation of Medici leadership from the aftermath of Giuliano di Medici’s 1478 murder at the hands of the Pazzi conspiracy to the equally untimely death of Lorenzo in 1492. During those tumultuous years, the sphere of Medici influence entrenched itself in an increasingly complex political net cast across the Italian peninsula.

As in prior seasons, the series presents itself with enough historical truth to be just shy of historical fiction. Even less historically accurate than the previous two seasons, it still manages to offer critical themes that define the historical realities of the second half of the 15th century. The challenging dichotomy of the temporal and sacred power of popes, the conflict between the papacy and popular religion, and the problems of mercenary armies beside the tangled alliances of the Italian states provide a proper historical framework. Along with familiar faces, some, like Bruno Bernardi, are purely fabricated.

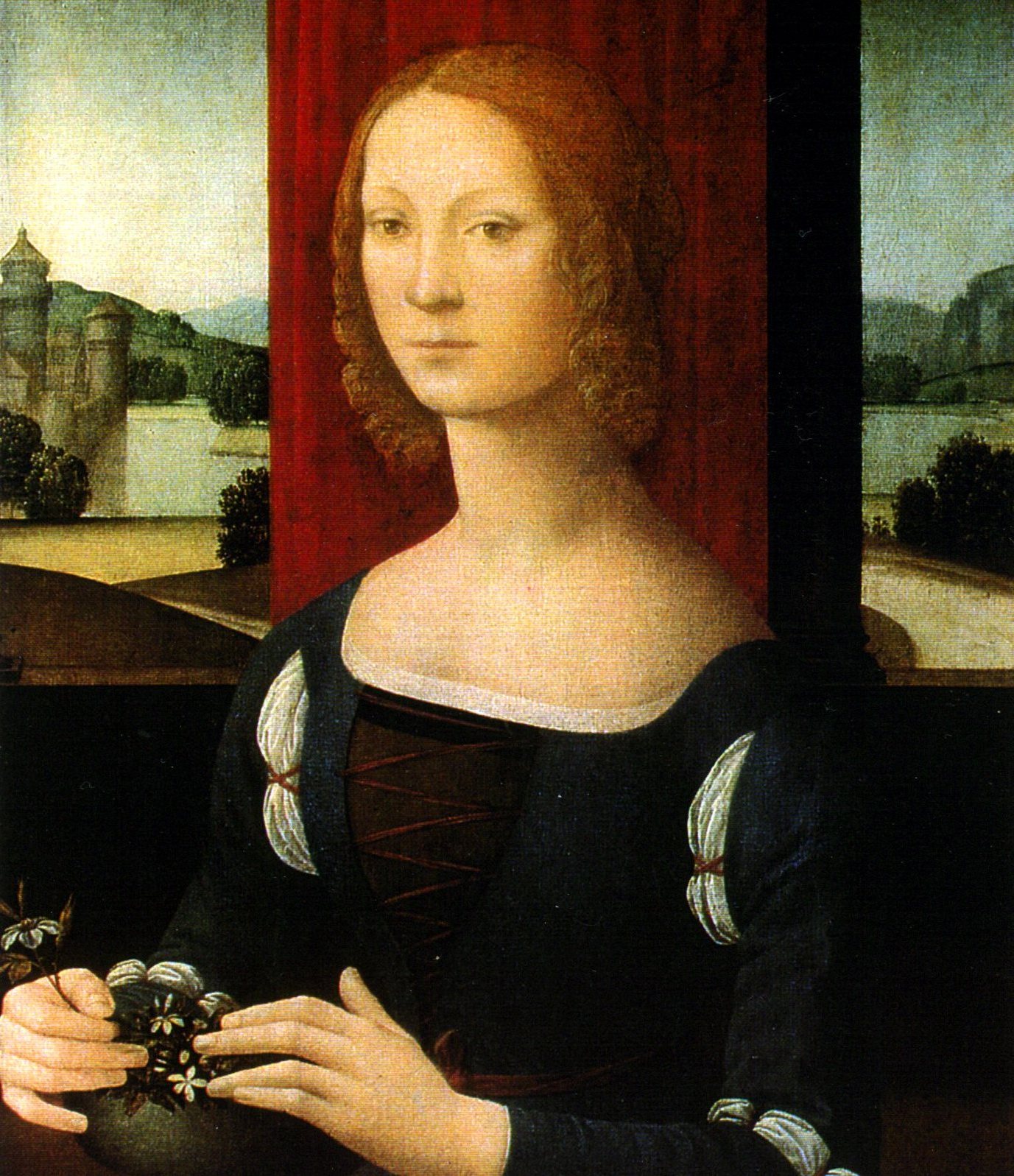

This series has a propensity to demonize Medici detractors who only want what the Medici have. Here we are presented with a repugnant, ill-tempered version of Girolamo Riario. This military commander failed to stop the Medici during the Pazzi conspiracy, but he has assumed a position of power at the right hand of uncle Pope Sixtus IV. In an effort to mend the papal relationship with Milan, Riario was married to Caterina Sforza. One of the most notorious women of her age, we are shown an abused Caterina Sforza suffering at the hands of her power-hungry husband. This characterization dreams of a better marriage, but the presentation of Sforza does a one-dimensional disservice to Caterina’s historical accomplishments. She cleverly survived imprisonment following the murder of her husband (who did not die at the hands of the Medici). Not only did she manage to arrange her own release and that of her children, she also negotiated for her young son to take command of Forli with herself as a powerful regent. She dedicated much of her time to the study of alchemy and botany. Unfortunately, we see none of this.

The cast of “Medici: The Magnificent”

Sforza’s character may be flat, but she illustrates an interesting theme that has come up many times in the series. Even those with socio-economic means were unable to decide the path of their lives. Being born to greatness, talent and power came with privilege and sacrifice. While this presentation is filtered by our contemporary lens, the seed of this discontent in humanism remains. Pico wrote, on Medici dime, that man is capable of all things, but here we see the reality versus that philosophical ideal. Lorenzo’s son Giovanni is sent to the curia when he wants to paint and Clarice has no say when her young daughter Maddalena is betrothed to the pope’s illegitimate son. This sense of obligation to follow one’s path in life is par for the course.

As too is the reality that 15th-century marriages were economic transactions. This season continues to struggle with the complex relationship between Clarice and Lorenzo, which comes into focus with the accelerant of Lorenzo’s mistresses and would-be mistresses. Here, their marriage improves through much of the season, but it is more off than on in historical documentation. This is very different from Lorenzo’s relationship with his mother Lucrezia, which was overwhelmingly symbiotic. Clarice Orsini is well-connected in Rome, but the notion that she is running the Medici bank to the point that Lorenzo doesn’t know that the bank is taking money from the city coffers or that the King of England defaulting on his loan was not the reality. The season’s tragedy is Clarice’s dramatic collapse and death. In actual fact, when she died in 1488, Lorenzo wasn’t by her side and he was unable to attend her funeral.

Besides a focus on Lorenzo’s private life, his statecraft is central. Warfare this season highlights the endemic use of mercenary armies by the Renaissance Italian city states. The use of paid soldiers proved complex to manage and, at times, damaging. Mercenaries have no loyalty without pay, and they can be bought. War between Florence and Rome (with Naples) is hinged on mercenaries.

Lorenzo di Credi’s Portrait of Caterina Sforza (c.1463-1509)

But diplomacy was at the core of Lorenzo’s magnificence as opposed to war. The series shines a spotlight on his trip to Naples to align Ferrante with Medici interests in Florence and away from papal interests. For Lorenzo, this was a brave (or reckless) suicide mission to save Florence from foreign domination. Celebrated because of his success, it serves as a reminder that the Medici could not rest on their laurels because they had no aristocratic legitimacy. Lorenzo was forced to be brazen and he benefited from Ottoman raids threatening Naples, along with Ferrante’s distrust of the pope’s loyalties. Florence was a better ally than an enemy. Lorenzo returned to Florence a hero, but we don’t see the golden age of peace: the series races ahead seven years, back to the threat of war with the papacy and the dying Lucrezia. Lorenzo’s mother was one of his most trusted and capable supporters, and the economic woes of the Medici bank made the loss of this matriarch even more affecting.

Death can cause power voids, and none more so that the death of a pope. Papal elections were marked by scrambles to secure one’s interests. There was no greater Renaissance powerplay than to elect a chosen pope. Medici efforts paid off, when Giovanni Battista Cybo was elevated to the papacy. However, despite Medici help, the new pope tells Lorenzo that he cannot repay loans to the Medici banks since has to pay his soldiers. The Medici can’t demand the payment without risking papal fury. Innocent VIII is not so innocent. Lorenzo protected the interests of the family in Rome in the longer term by positioning his second son Giovanni and Giulio, the illegitimate son of his slain brother, in the priesthood and toward the red cardinal hat. Popes wield the power of excommunication. This damnation was a fate worse than death, especially for leaders because their people would rise against them rather than face hell themselves. Medici popes seeking diplomacy had a new weapon in their arsenal.

This series reminds us that, even with growing Medici power, challenges to their authority remained. Savonarola risked papal and Medici fury. This Dominican friar appealed to those seeking piety. He espoused radical ideas to large, agitated crowds of Florentines. Savonarola was a complex figure who, like Sforza, isn’t given a great deal of depth in Medici. He was a foreboding man of innumerable faith, but one who couldn’t tolerate corruption in the institutionalized church. Savonarola is far better understood if one steps back and considers that this priest was one of many lightning strikes on the horizon during the Reformation storm before Luther would hit the rod in the near future. Savonarola’s bonfires of the vanities were a direct attack on Medici and the 15th-century Renaissance humanist ideal that they promoted. The series leaves us with an unfinished story. We last see him at Lorenzo’s death bed offering last rights, but Savonarola would seize control of Florence before facing a grisly execution on the orders of the Borgia Pope Alexander VI in 1498.

Bronzino and workshop, Portrait of Lorenzo de’ Medici, 1555-65.

While this season is heavily focused on war and peace, it contains a peppering of cultural history. Botticelli is in the background, reminding us that gone are the carefree days of the Platonic Academy at the Careggi villa. As we see in Medici, Botticelli became more devout and enamored with the teaches of Savonarola, which caused him to drift away from Medici secularization and classicism. Leonardo da Vinci is rightly shown as a man of science, who is less god-fearing and eager to defend his secular worldview. A young Michelangelo makes only cameo appearances, but it is a story that his contemporary Vasari recounts from Michelangelo’s interactions with Lorenzo. Lorenzo’s cultural magnificence rests on their talented shoulders.

At only 43, Lorenzo’s life was cut short by arthralgia. The hereditary Medici disease caused a painful end and a race against time. The series conclusion leaves us with false hope. The family is shown gathered in unity around Lorenzo’s death bed, but notably absent are his children (he had 10). Despite being symbolically united on screen, the Medici could do nothing to stop the Catholic Church from shattering under the weight of the Reformation, the republican ideal of Florence would soon be destroyed and the city-states would be crushed at the hands of the large imperial armies from the north during the Italian Wars. The Medici would be pushed out of Florence two years later, when it was clear that Piero, an unfortunate Atlas-like figure, was unable to fill his father’s shoes.

As the season draws to an abrupt close, glimpses of a young Michelangelo and Machiavelli point toward the historical future. Their humanism was much darker in the wake of the destruction of Renaissance idealism. The Italian Wars would cause an existential crisis that brought the Italian Renaissance to its knees. Even the Medici popes, Leo X and Clement VII, inherited the Reformation, an economic and political crisis that culminated in the Sack of Rome in 1527. But in 1492, we are left with Lorenzo’s hopeful last testament that what happened in 15th-century Florence cannot be erased. Lorenzo was right. As a global crisis shakes our sensibilities, this Lorenzo appears on our screens like the return of the prodigal son. Who wouldn’t want a Medici lighthouse in 2020 and a little magnificence to boot?