Ian Kiaer is a British artist who has exhibited throughout Europe and North America. In 2009, he was accorded a one-man show at Turin’s prestigious GAM, Galleria Civica d’Arte Moderna, and last year one leading public venue in Paris invited him to show. His next stop will be Germany, but until late September he has two intense and challenging installations in the pocket spaces of BASE in San Niccolò. In some ways, Kiaer’s work is uncompromisingly conceptual; in others, it is visually playful and exploratory. Having spent time in this show, the visitor alone decides which route to follow to reach an interpretation, then leaves with a head brimming with propositions.

The street door leads into the first of two narrow rooms. Lying on the grey concrete floor of the first chamber of BASE’s compact interior are two objects that immediately dispel the aura of art, its style and finish, associated with galleries in Florence. The first is an inflated plastic bag, ultra-light and oversized even for a bin liner. Its sherbet-yellow surface stands out against the cold hard ground, while its shape, bloated and distended, makes a slight ruffling sound as it quivers like a quietly anxious creature. Out of it trails a cable to a wall plug from which electricity flows back inside to power a fan you cannot see and a small, illuminated screen that is just visible through the translucent shell.

As thoughts stir about the bag’s purpose, the eye moves to the second object placed nearby. This small construction, by contrast, is rigid and box-like. Quite crudely made in what looks like balsa wood, clear plastic, card and tape, it has two blocks connected by a shallow rectangular base that raises it slightly above floor level. There is colour here, too, but it is dull and industrial, and although there are transparent sides, the visitor would have to bend down low to see inside.

Kiaer, Ping, murmer, 2019, at BASE, Florence, 2019. Copyright: Ian Kiaer. Photo: Leonardo Morfini

Gone are the usual apparatus of galleries. There are no plinths and barriers. This could be a meeting on the street, among the materials found everyday around the home or workplace. The objects are a little shoddy and may have been retrieved from a bin or have been used elsewhere already, maybe in other exhibitions as different objects. The plastic, card and wood are scuffed with wear that is too ingrained to have occurred during the life of this installation alone. And they could take on another function at any moment. On the next visit, this assembly might have changed. At least, that suspicion exists because the gallery has the feel of a workshop or laboratory, a place where experiments take place in aid of scientific enquiry. Or this space could be backstage at the theatre where props are prepared for an absurd play or as minimal scenery.

A sensation of time, even of secret history, exists in parallel with the new uses that Kiaer has introduced. With time, and the random impressions it leaves, comes the space in which unexpected thoughts surface. They connect with personal experiences of the world that no other visitor can share. In a sense, Kiaer’s unexpectedly spare room lives more in the mind than in the real space, as if it is grounded in the lives of everyone who looks at it.

Describing the two objects as sculpture seems insufficient. They suggest other things as well: architecture, for instance. The blocky piece is made up of levels that are probably floors separated by little Perspex windows. Even the strips of cream-coloured tape resemble blinds, as if the miniature interior of uprights and beams needed protecting from strong light.

The ballooning bag is more radical, being both organic and habitable (there is a screen inside). It recalls a type of building increasingly seen in cities, able to go anywhere to solve housing emergencies, host public gatherings or provide sports events with a covered setting. Watching the shape billow with air brings thoughts about the potential space inside if it was full-sized. Both appear temporary, lightweight and subject to alteration. Kiaer offers a bird’s-eye view for comparing the structures. No question arises of stepping inside either except with the imagination, the way dolls’ houses are travelled. Or paintings. If we stretch our imaginations, this installation might be a three-dimensional painting or, at least, the model for one. Models by architects, planners or hobbyists project the mind forward into another space and time; it might be the future or pure fantasy. That is when ideas either lift off the plan into reality or remain as unfulfilled visions, still thrilling but only in an abstract way.

A similar process helps Kiaer create new work. During his 20-year career a recurrent stimulus for Kiaer has been the visionary ideas in modernist architecture. He frequently quotes them. We think of quotation in terms of speech and writing but Kiaer expands that reach into the arts, perhaps because they also have “languages”. Kiaer often refers to architects who took great steps forward in how people make and inhabit buildings. As a result, Florence is an ideal setting for his work. The city’s streets still harbour quantum leaps in architecture from the past by Brunelleschi, Alberti and Michelangelo. These artists were the cutting edge of the avant-garde of their time—and clashed with contemporaries puzzled by their ideas.

Close to our time, Giovanni Michelucci and his team broke new ground with their interwar train station at Santa Maria Novella, which confirmed a place for modernity in historic Florence. Their ideas helped set in motion attitudes that led to the far-sighted concepts developed co-operatively in the 1960s and ‘70s. Florence’s own highly theoretical architettura radicale of Archizoom or Super Studio, although little was built, included blow-up buildings and megastructures that outpaced technology. Although their extraordinary vision fed into the recent extraordinary transformation of city centres, their idealist plans for new ways to live and work collaboratively never left the drawing board.

So, is Kiaer’s installation about new art, missed arcadias, dream buildings or recent design? Like the yellow inflatable, these categories seem to want to blow away. Kiaer is interested in how we arrive at the meanings for what we see or hear. Those meanings are not always fixed. Tactile objects might suit the thought process better than words; some ideas, even beliefs, go too deep to articulate. If they could be described, then they might resemble the writing of Samuel Beckett.

The tense, minimal prose of the Irish playwright and author was simultaneously zany and sober, witty and profound. At first his writing could strike readers and audiences as gibberish. We speak, write and hear the same words but seldom in the way Beckett uses them. As a result, his work does not initially communicate with us. Then a pathway opens to piecing together an interpretation; it might take shape through the sound of his words rather than their known definitions, or by listening to their rhythm or repetition, or the interval between phrases.

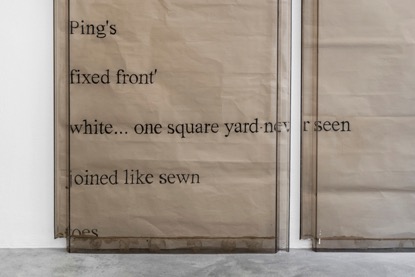

Meaning steps out like a mind waking into consciousness. In the second room at BASE, Kiaer explores this phenomenon with phrases extracted from Beckett’s story, Ping. The lines written in large letters on poster-sized sheets of creased brown packing paper hung on the wall express very little directly: “white… one square yard-never seen” reads one, “joined like sewn” runs another. Ambiguity does not stop there. The words on show resemble type in a book but are visibly handmade; they have been painted to look like print and ranged to the left like poetry so that an immensity of space surrounds them.

Like Kiaer, Beckett crossed barriers and mixed shapes. He was multilingual and wrote in French, translating himself. His “literature without style” is quintessentially modern and has found its place in popular culture. His story was first published in 1966. The full text is short and sparingly punctuated. Kiaer’s choice of quotes sprinkled onto the sheets make the original shorter still, even terser and more ambiguous. His paintings have an unusual layout. The words appear poorly aligned with the paper as if produced from a badly loaded printer. The text drifts off the bottom edge and collides with the frame almost before the eye can read it. Perhaps the lines will eventually scroll upwards in the manner of a newsreader’s autocue prompt? At that time, maybe the empty expanse of unpainted paper will fill with meaning.

Another awkward is the plastic covering to these paintings. At points, it fails to overlap the paper, and elsewhere its edge spills over on to the wall. Cloudy with scuffs, cracks and scratches it is tattooed with its own anonymous past, forlorn with the marks of exposure to careless handling. (The artist reuses Perspex frames from British bus shelters.) Kiaer here overlays one story—Beckett’s—with another written by time. Each has a manuscript of its own, devoid of style, that sets the tone of the onlooker’s response.

Kiaer tests the rules of recognition; that was also Beckett’s way. Likewise, Kiaer is an artist not afraid of creating encounters that test the onlooker’s ability to put his or her reaction to it into words. How many ideas can an artist fit into a room with dimensions no larger than an edicola? The answer is currently filling the space at BASE.

Ian Kiaer: Ping, Murmer

BASE Progetti per l’Arte until 21 September 2019

Via San Niccolò 18r