As well as the calamitous flood, late 1966 saw the emergence of ground-breaking ideas about architecture in Florence. The spirit of collaboration that lifted the city’s treasures out of the disaster also released outstanding creativity from young architects and designers. They worked collectively in groups and Florence became the centre of their radical activities—“radical” because the groups proposed extreme shapes and structures, and embraced design as a vehicle for social justice and political change. The current show at Palazzo Strozzi’s Strozzina charts the movement’s short life and continued relevance.

A six-minute video follows a young man’s behaviour as he sits at a drawing board. He clips his fingernails and sifts through papers in his wallet; he lights a cigarette and sketches a figure; he scratches his head—anything, in fact, but take up the traditional instruments of his profession set out in front of him.

The man is Gianni Pettena and his film, Intens (1971), was made at the height of Architettura Radicale. Pettena remains a leading proponent of this anti-movement that sought a new social role for architecture. It emerged from the social tumult of the late 1960s and its radicalism was rooted in the ethic of pop culture.

Instinctively critical of the status quo, it opposed the mass-produced sterility they saw in rationalist postwar modernity. Pettena was once described as “an architect on strike” because his practice veered closer to the conceptual, environmental art of galleries and “happenings” than to construction. That perspective summed up the radicals: recent graduates of Florence University, they built little but had rich imaginations.

Radical design flourished briefly in France, Spain and Eastern Europe, but its most challenging manifestations were in Italy, and nowhere more prominently than in Florence. Often working in the city’s medieval centre, many formed groups with futuristic names like Archizoom, Superstudio and Zzigurat that rejected the established heroic image of the solitary architect, which had dominated since the Renaissance. Each collective had a distinct approach. Some absorbed Umberto Eco’s semiotics; Italian Futurism and British conceptual architecture influenced others; and advanced notions about industrial design and education by Ettore Sottsass and others affected still more. Underpinning all was a subversive philosophy that disregarded distinctions between architecture, design, painting, graphics, sculpture and cinema.

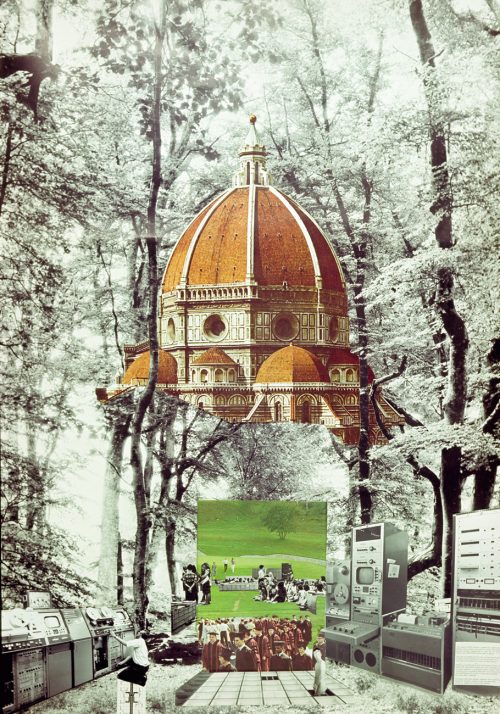

In this multidisciplinary atmosphere, crosscurrents proliferated. Superstudio, featuring Adolfo Natalini, Cristiano Toraldi di Francia and their colleagues, developed ideas in outstanding collaged images; Gruppo 9999 projected abstract patterns at night onto the Ponte Vecchio; Archizoom made kitsch lamps satirising the “American Dream” concocted by Hollywood; and Studio UFO carried huge inflatable objects bearing slogans through the historic centre. One of these giant structures, Uboeffimero 6 (1968), currently floats above the palazzo’s courtyard.

Interventions of this type provoked contrasts between present and future. Analysing the state of the world in the midst of fading prosperity and civil unrest at home, and inequality and war abroad, the groups visualised a future world aided by technology. Design that was flexible and adaptable challenged “good taste”, took account of the user more than the maker and removed obstacles to freedom in life.

One vision of an urban utopia was Archizoom’s No Stop City (1970), in which advanced systems would eliminate the need for a centralised metropolis. Instead, cities consisted of homogenous elements adapted to a variety of uses. Residential units and organically shaped open spaces were placed haphazardly over a grid structure, allowing for a large degree of freedom within a regulated structure. The plan was strongly ironic, but it advanced serious new conceptions of life and revolutionary urban forms.

The movement was overtly political and designed with ingenuity; fantasy, sustainability and emotion were more important than utility and reason. Critical of capitalism’s emphasis on production, waste and consumption, Pettena and his fellow proponents used theories and images rather than buildings to promote the humanitarian side of architecture and design. Their ideas on urban planning acknowledged few limitations, and because their mischievous, disruptive approach was illustrated in influential magazines like Casabella and Domus, their research became widely known professionally in Italy and Europe.

Not every proposition by radical architects was hypothetical. At the Florence disco Space Electronic, audiences encountered furniture by 9999 in the early 1970s made from washing-machine drums and fridge casings, while at nearby Mach 2 pink strip lighting and bright yellow handrails guided people through Superstudio’s pitch black, underground nightclub interior. In these socially neutral settings, if nowhere else, boundaries could be broken. The Piper in Turin and Rimini’s L’Altro Mondo were transformed by young architects, and perhaps the most astonishing was Bamba Issa in Forte dei Marmi. Here the team that composed UFO devised exotic storylines that evolved over three years. Using low-cost materials, they invented an African desert, a search for oil, a partly destroyed ANAS house, polyurethane ruins and a Doric temple. With records bought in London further enlivening the surroundings, the venue was a huge success.

This exhibition bristles with the energy of fast-moving, transgressive creativity, barely diminished after almost 50 years. Pettena’s hinged and portable Wearable Chair (1972) in plywood is part body art and part practical application: simultaneously a performance and an extra seat on the bus. The wave-silhouetted Superonda sofa (1967) by Archizoom would not look out of place in a contemporary showroom, while 9999’s Vegetable Garden House (1971), where residents could grow their own produce in homes that balanced nature and technology, offered a model of sustainable living decades before mainstream planning explored the possibility.

Like so much else, that project did not go into production; commercial viability was never a priority for radical architecture. Although some furniture found a market, most ideas remained unachieved. The movement had faded by the late 1970s and the irony is that prototypes and artwork produced by the different studios are now highly prized by collectors. As this show proves, the entire movement is once more the subject of worldwide critical interest. The prime motivation of these architects remains undimmed: architecture shapes our lives and can make them better.

Radical Utopias – Beyond Architecture 1966-1976

Until January 21, 2018

Palazzo Strozzi, Strozzina, piazza degli Strozzi, Florence