Halina finished her shift at Signora Ludovisi’s at 5pm. In ten minutes she had combed her long curly red hair and put it up into a ponytail, brushed her teeth and changed her top. She walked quickly down the steps of the palazzo that, with the exception of Signora Ludovisi and Signor Bisconti, only housed offices.

Walking out of the doorway, she turned toward the apartment window for no particular reason. Her gaze fell for a second on number 24 rosso. She smiled, remembering how long it had taken her to find the address in piazza Santa Maria Novella when she had first come to Florence two years ago.

Her date with Helver was at 5:30pm in piazza Stazione, at the ATAF bus stop in front of the tourist information office. Helver was coming from Pisa by train. At least that’s what he had told her.

As soon as she sees him, she realizes just how happy she is. She’s happy because she likes Helver, but mostly just because he’s there. She wasn’t sure he’d come; some of their dates hadn’t happened because he’d had “complications” at the last minute. At least that’s what he had told her.

Helver hugs and kisses her shamelessly. He has the ardour of a teenager, though he’s over sixty. He carries off his pigtail, baldness and white whiskers with aplomb. His dark complexion is more apparent on his hands, in contrast with the lightest of nails, almost white.

Now they walk along via degli Avelli, the street leading into piazza Santa Maria Novella, full of tourists as usual in the spring. Halina likes the idea that she’s also a foreigner, but that, with this square, she has the familiarity of a Florentine. She likes to observe the wonder of tourists in front of the basilica’s facade, because with them she relives her own awe every time. Helver isn’t Italian either. He was born and grew up in Italy, but like other Romani he doesn’t have Italian citizenship. He’d told her he was stateless, free.

Walking, they leave the basilica’s facade behind them, moving in the direction of the benches in the middle of the piazza. It’s only the end of May, but it’s a hot, sunny day. The benches are scorching. Halina thinks that iron and glass benches would be a good fit in her city, Gdansk, not in Florence where temperatures reach 40 degrees in the summer. They keep walking past the benches.

Helver walks, his arm around her hip, then he takes her hand and laces her fingers with his own. He’s impatient, every few steps he stops and kisses her. Halina is overcome by the passion, but when they walk in front of the door into the palazzo where she works she cannot help but notice a bag of rubbish placed on top of one of the two brass pots at the sides of the entrance. Who left that there? Signor Bisconti’s caregiver? She’d like to pick it up and throw it into the underground bins less than thirty metres away, but she doesn’t.

They reach the steps in front of the loggia of the Museo Novecento, on the opposite side to the basilica. They sit on the steps.

“Helver, do you know how to draw?”

“No, I’ve never known how to draw.”

“Helver, I like you, you know.”

“Yes, Halina, I know and I keep asking myself why.”

Halina often asks herself the same thing. She knows that Helver is a liar. They have been seeing one another at least twice a week for almost four months and they speak or write to one another four or five times a day. But she only found out a week ago that Helver has a wife and four children. He confessed after she had asked him a few questions that weren’t even that direct.

But Halina knows why she likes Helver. When she was sixteen she fell in love with a Romani boy who lived in her town and had an Italian name, Mauro. He was a wonderful person and she adored him, but for her family the relationship was unacceptable. Once he’d given her a pair of huge round copper earrings, which she still wears from time to time.

–

Barry is standing outside the pub with a pint of Harp Strong in his hand. It’s his first break since he opened the place at midday. But he got up at 7am, as usual. Twenty-five years living among Italians has not changed his style. He always wears white socks and sandals, t-shirts with beer brands and trousers of an indefinable colour that are always too long.

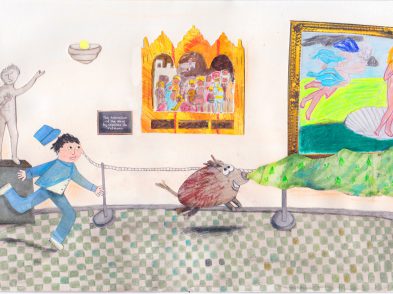

In moments like these he enjoys observing the piazza, seeing how its beauty attracts people, all so different, all wanting to capture a moment of their existence in a snapshot with the Basilica of Santa Maria Novella in the background. The Museo Novecento doesn’t hold the same fascination. Its steps attract artists and students wanting to portray the basilica and who often, at the end of the day, treat themselves to a beer in his pub.

Wait a minute, who’s that on the steps today? That nice Polish lady who works in the palazzo opposite who’s been to the pub with her friends a few times… Who’s that with her? No, it can’t be! That gypsy who came to The Fiddler’s Elbow that one but memorable time with a woman and a much younger couple, drinking an incredible amount of beer and then arguing over the bill. Where would they have met?

Barry feels a mix of annoyance and admiration at Helver’s self-assuredness. He’s had plenty of opportunities, between orders, bills and change, to engage the attractive woman in conversation, but he’s never done so. He’s finished his pint and with the pint his break. It’s time to get back to work.

–

“See how time flies and how life flees”, wrote Petrarch in his 14th-century Canzoniere. A son of Florentine parents, he was born, grew up, lived and finally died outside Florence, a life in exile.

How time has flown since that May afternoon two months ago. It’s Friday, July 22. Piazza Santa Maria Novella is still full of tourists, even though it’s raining. Halina is on the bus, nearly at Bologna. Her Eurolines bus left two hours ago, at 14:25 in piazza Stazione – she’s going home for a week, to Poland. She hadn’t expected Helver to come and say goodbye. When she saw him there, in the rain, unusually silent, holding a small bunch of gerberas and wearing those light blue moccasins splashed with white paint, she was touched.

She struggled to hug him because she was holding her bag and umbrella, and Helver, stiff and immobile, hadn’t helped. When he moved he had hugged her in slow motion, still standing upright, but without turning into her. Bowing his head slightly, he had whispered in her ear: “Halina, take care of yourself… And call me as soon as you get back.” Halina replied by hugging him tighter and pressing her lips to his cheek. Then she turned and boarded the bus, whose engine was already running. Helver was still holding the gerberas.

It has been raining for five days. The rattle of the rain and this 24-hour journey come at the right time to sort her head out, thinks Halina. But when the bus begins to skid, before overturning, her thoughts go straight to the presents in the luggage compartment, which she’d bought for her husband and daughters.

–

It’s 16:30. Helver has just got off the train at Pisa Centrale. Here too, as in Florence, it’s raining in floods. You’d have to go back to 1932 to find such a wet July. Helver doesn’t care about the rain, or about anything else. He’s agitated. He can’t believe that he invented an excuse not to go to work – if painting the walls of an oratory at six euro per hour cash in hand can be called work – to go to Florence just to say goodbye to Halina. But he’d done it; he couldn’t have done otherwise.

Halina had won him over with her strength. The story about his wife and four children was tried and tested; it had always worked in the past. When he had played that card, bored of a relationship, all of his lovers had left him. Some sooner, some later, some angry, others with resignation, but they had all left him.

With Halina it had been different. First of all, he really liked being with her. He had brought up the story of the wife almost out of habit, an affectation perhaps, but with genuine dread. And Halina had floored him. Once Helver had delivered his line, Halina had looked him in the eyes for a few seconds and then, taking him by the hand, said, “How much pain you have inside, Helver, how unhappy you are.” Then she’d kissed him tenderly on the lips. In that moment Helver had felt all of his unhappiness and loneliness, and even the possibility to tell someone the truth, even though he hadn’t done so in the end. A smile now cuts across Helver’s wet face as he crosses the road from behind the bus shelter, not checking for cars on the road driven by the rain.

–

Halina. Barry has found out her name at last. She came to his pub yesterday evening towards 5pm. She’d ordered a Kilkenny Strong, an excellent choice, for a woman with character. This time it hadn’t been hard to strike up a conversation. The pub had been practically empty due to the rain and it was thanks to the rain that showed no sign of stopping that they’d started talking. It’s not true that only the English talk about the weather. Halina had told him that she’d just finished her shift and that tomorrow she’d be leaving to go home for a week.

Seeing her close up Barry was struck by the intensity of her eyes, the colour of her hair, the same shade as the beer she was drinking, and by a scar on her face. His gaze must have lingered for too long on the scar because, at a certain point, Halina said, “I was bitten on my face by a dog when I was 18 months old.” She added, “Every scar is God’s signature.” Barry hadn’t really understood what she meant, but he’d smiled.

The pub had filled up in the meantime. Barry had started serving people and Halina had finished her beer. She’d stayed there in silence for a few minutes, the empty glass in front of her, while the noise level rose. Then she’d got up, gone to the till and paid, even though Barry had insisted on standing her the pint. Before she left he’d shaken her hand, holding it a bit too tightly and for a bit too long, saying, “Halina, as soon as you get back to Florence, come to the pub and maybe we’ll be able to have a beer outside if the weather’s better.” Halina had nodded and left.

–

Signora Ludovisi screws up her eyes and wrings her hands together, kicking her feet as she shouts. She’s angry because Karolina, Halina’s replacement, doesn’t understand what she wants. Karolina came to Florence two months ago and still doesn’t really speak Italian. Neither does Signora Ludovisi since two months ago, when she’d had another stroke. After a while Karolina begins to understand what the lady wants from her gestures. She moves the wheelchair next to the wind and opens the drapes. Signora Ludovisi calms down immediately. Now she observes the piazza, observes the rain. How piazza Santa Maria Novella has changed, how it’s always the same in the driving rain. Her memories go immediately to 1966, the year of the flood. Fifty years have passed but in her mind full of holes the memory of that American student is still alive. They called them “mud angels” and he was one of them. What she doesn’t remember is how their time together ended. Had there been a relationship? How can you remember a face so well and not remember the rest? Maybe nothing had happened. Memories, wishes, regrets get mixed up, but maybe it’s not really that important, thinks Signora Ludovisi, as she scratches an ear.

Translated into English by Helen Farrell

If you enjoyed this short story, then you’ll love The FLR – The Florentine Literary Review: six short stories and 2 poems by contemporary Italian authors lovingly translated into English.