On December 10, 1942, a

dinner at the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel in Manhattan replaced the annual

Nobel Prize award ceremony in Stockholm, which had been suspended in

1939 because of World War II. Eleven of the 28 laureates then living

in the United States attended. Most of them had fled Europe to escape

Hitler and had become vital to the Allied war effort. One of them was

Enrico Fermi, the Italian physicist known as the ‘father of the

atomic bomb.’

The

son of a railway employee, Fermi was born in Rome on September 29,

1901. As a teenager, he became fascinated by mathematics, having

bought two books in Latin on the subject at a street stall. Guided in

his studies by an engineer friend of his father’s who recognised

the boy’s extraordinary intelligence, Fermi won a place at the

prestigious Scuola Normale Superiore in Pisa and graduated in physics

from there in 1922. For the next two years, he taught at the

University of Florence and then became professor of theoretical

physics in Rome. For his research there, focused on neutron

behaviour, he won the Nobel Prize in physics in 1938. Concerned

because the Fascists had recently passed anti-Semitic laws in Italy,

after accepting his award in Sweden, Fermi, together with with his

Jewish wife and two children, escaped to the United States. There, he

continued his experiments on nuclear fission as a professor of

physics at Columbia University in New York where he and his colleague

Leo Szilard co-invented the first small nuclear reactor, which Fermi

dubbed the ‘pile.’

Realising both the

potential of an atomic bomb to bring the war to a close and the

catastrophic outcome if the Germans developed it first, the US

government poured 2 billion U.S. dollars into the bomb’s

development. Fermi was appointed head of the Manhattan Project at the

University of Chicago, where, on December 2, 1942, he and his team

produced the first nuclear chain reaction from the full-scale nuclear

‘pile’ they had built in a squash court under the stands of the

university’s football stadium. From that moment on, the

construction of the bomb was merely a matter of assemblage. To

celebrate, Fermi opened a bottle of Chianti, drinking it together

with his fellow scientists from paper cups.

In 1944, the project was

moved to a desolate area in the American Southwest, Los Alamos in New

Mexico, and on July 16, 1945, the first atomic bomb was detonated in

the desert at Alamogordo Air Base. Less than a month later, President

Truman announced that an atomic bomb had exploded over Hiroshima, its

devastating consequences only becoming fully apparent some time

later. It was soon followed by another bomb, again dropped on Japan,

this time at Nagasaki.

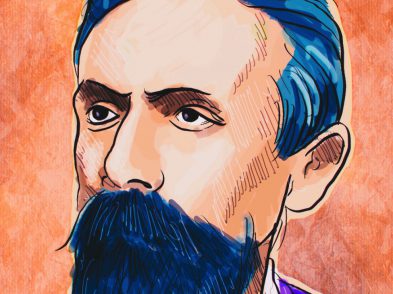

A dark-haired man of

average height with piecing grey-blue eyes and a resolute manner,

Fermi was not always easy to work with. Because he was seemingly

infallible, he was nicknamed ‘the pope’ by his fellow emigré

colleagues, Hungarians Szilard, Eugene Wigner, John von Neumann and

Edward Teller, whom Fermi called ‘the Martians’ because of their

superhuman-like minds and their strong accents when they spoke

English, and German Hans Bethe; together they formed the backbone of

the ‘bomb squad.’ Another colleague, Sam Allison said of him,

‘He’s a tougher character [than I] and good at saying no. He

refused to do administrative work. He doesn’t have a phone and

refused to have a secretary. General Groves [military chief of the

Manhattan Project] hates my guts. But he hates Fermi’s guts worse.’

Not surprisingly, his wife, Laura, painted a softer picture of him in

her book Atoms in the Family,

describing how her husband suffered far more from his shortcomings in

his preferred sports of skiing, swimming and mountain climbing than

from any setbacks in his scientific experiments.

Nonetheless, on that

December day in Chicago in 1942, when Fermi achieved the first

self-sustaining nuclear chain reaction, the world changed forever.

The Atomic Age had begun. It triggered the arms race and the

knowledge that, for the survival of the planet, even an uneasy peace

was better than any prospect of future global warfare.

In fact, the jury is still

out on whether the splitting of the atom brought with it lasting

benefits, and the pro and con nuclear debate continues to rage on.

Supporters maintain that it opened the way to harnessing energy for

peaceful purposes, for example, its use in nuclear power plants.

However, after incidents like the 1986 accident in Chernobyl and

multiple failures in the reactors at Fukushima following the recent

Japanese earthquake and tsunami, adversaries say its disadvantages

heavily outweigh its advantages. Still others insist on its merits,

pointing to advanced techniques in nuclear medicine, breakthroughs

that arrived too late to help Fermi, who died, aged 53, of stomach

cancer on November 28, 1954, probably caused by his exposure to

radiation.